Fisheries Management & Legislative Report

Contents:

In the last newspaper I was talking about how much we need to learn about the producing areas. Some people could not resist sending me the latest release from Maryland about closing their spring trophy fishery. In the release Maryland contends they provide 70 – 90% of the coastal migratory stocks. If Maryland is still making that assumption with all the tagging data available, that is just more evidence that we need to study the other producing areas and find out what they are actually contributing to the coastal migratory stock. We all know Maryland is not contributing 70 – 90% but we need hard data to make good decisions. It has come to my attention that ASMFC has decided to dedicate some staff time to look into this. I want to be clear. I was never looking to catch smaller fish in our producing areas. I just want to know what we need to do along the ocean if other areas are contributing more.

There are two addendums for Eels going on at the same time. Addendum VII deals with the quotas for yellow ells mature ells and Addendum VI deals with glass ells quotas (juvenal ells migrating into freshwater to mature). The NJ hearing on Addendum VII already took place but you can go ASMFC Web Page and find other dates to attend. There is only one hearing on Addendum VI on February 28.

JCAA has always been concerned about the harvesting of glass eels. Glass eels are even more endangered due to global warming. Global warming has impacted most species I deal with causing them to move further north as the waters warm. Glass eels are impacted by global warming heating the areas where they mature. The problem is glass eels are totally dependent on the Gulf Stream. They are species that grow to maturity in fresh water and migrate to the ocean to spawn in the Sargasso Sea. After the adult eels spawn, they disappear and the eggs and embryos float around in the Gulf Stream. It takes about a year for the full cycle and in the past the Gulf Stream has been consistent in the speed at which it travels. The historic pattern is for the glass eels to reach the stream where they need to grow in the early spring when the water is high so they can navigate upstream. The ice pack in Greenland is melting and making the Gulf Stream go slower. If the glass eels return to their growing space at the wrong time, there will not be enough water for them to reach the appropriate spot. I have included two articles that talk about the collapse of the Gulf Stream. If this happens it will have a huge impact on every species dependent on the Gulf Stream.

The worst part is the impact this will have on the climate in Europe, returning it to a much colder time. Please read these articles. Because it takes 19 years for glass eels to mature and return to the Sargasso Sea, any change in climate can have a huge impact on them. With the support of the NJ Legislature, we have ended the harvesting of glass eels here.

The prices Japan pays for glass eels makes it an extremely profitable fishery. Currently Maine is one of the few states that still allows the harvesting of glass eels for the overseas markets. With the collapse of the lobster fishery, the glass eel fishery has become even more important in Maine. In the long run, the health of birds and fish in our rivers, streams and lakes is more important than the short-term financial gains by a few individuals. I will be testifying on this information and am hoping there will be a cutback on the harvest in Maine. We cannot take a chance.

Arlington, VA – The Commission’s American Eel Management Board has released Draft Addendum VI to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for American Eel for public comment. The Board initiated the addendum to address Maine’s glass eel fishery quota, which expires at the end of 2024. Draft Addendum VI presents options to set Maine’s quota as well as the number of years the quota would remain in place once it is implemented, and whether or not an additional addendum would be required to maintain the same quota for subsequent years.

Addendum V, approved in August 2018, maintained Maine's glass/elver eel quota of 9,688 pounds, previously established by Addendum IV, and specified that the quota be set for three years (2019-2021). The quota was extended for an additional three years (2022-2024) through Board action in 2021. Since Maine’s current glass eel quota of 9,688 pounds expires after 2024, the Board initiated Draft Addendum VI to establish a quota for the 2025 fishing season and beyond.

One virtual public hearing has been scheduled to gather public input on Draft Addendum VI on Wednesday, February 28, 2024, from 4-5 pm EST. Details on how to register and attend the hearing are provided below.

Webinar Instructions

In order to provide comment at any virtual or hybrid hearings, you will need to use your computer (voice over internet protocol) or download the GoToWebinar app for your phone. Those joining by phone only will be limited to listening to the presentation and will not be able to provide input. In those cases, you can send your comments to staff via email or US mail at any time during the public comment period. To attend the webinar in listen only mode, dial (562) 247-8422 and enter access code 960-376-742.

To register for the public hearing webinar, please click here. The hearing will be held via GoToWebinar, and you can join the webinar from your computer, tablet, or smartphone. If you are new to GoToWebinar, you can download the software here or via the App store under GoToWebinar. We recommend you register for the hearing well in advance of the hearing since GoToWebinar will provide you with a link to test your device’s compatibility with the webinar. If you find your device is not compatible, please contact the Commission at info@asmfc.org (subject line: GoToWebinar help) and we will try to get you connected. We also strongly encourage participants to use the computer voice over internet protocol (VoIP) so you can ask questions and provide input at the hearing.

Submitting Comments

The Draft Addendum is available at this link or via the Commission’s website. Public comment will be accepted until 11:59 pm (EST) on March 24, 2024, and should be sent to Caitlin Starks, Senior FMP Coordinator, at 1050 N. Highland St., Suite 200 A-N, Arlington, Virginia 22201; or at comments@asmfc.org (Subject line: Glass Eel Draft Addendum VI).

For more information, please contact Caitlin Starks, Senior Fishery Management Plan Coordinator, at cstarks@asmfc.org.

Things Jim Hutchinson Needs to Know

This is in response to a February 2024 Editors Log by Jim Hutchinson. In this article, Jim completely rewrites the history of the subway cars debate that began in November of 2000. I have included 3 articles from the JCAA Newspaper of 2001, a July 2001 letter from the State of Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, and Jim’s article from 2024. There are other articles in the January 2024 JCAA Newspaper. In addition, I talked to several outdoor writers and Gary Caputi who was in attendance at the June 2001 meeting with me, Dery Bennett and Cindy Zipf. Please read the articles included so you have a complete picture of what is happening. I did not want to revisit the subway car issue. I thought it was finally put to rest. I would like to continue working with Clean Ocean Action on issues that are important to all of us including offshore drilling and ocean dumping.

- Jim Hutchinson should know that JCAA worked with Clean Ocean Action since it was formed around a variety of issues including ending ocean dumping and wood burning. JCAA worked on some of those issues along with Len Belcaro and the Thousand Fathom Clubs North and South and Cease Ocean Dumping before Clean Ocean Action was ever formed.

- Jim Hutchinson should know that Gary Caputi, Dery Bennett, Cindy Zipf and I did meet before the summer of 2001, trying to come to an agreement on the use of subway cars. During the meeting I got a call from the Governo’s Office asking if I knew about the asbestos contained in some of the cars. JCAA was aware that the asbestos was in tiles which were removed and in the epoxy that was between the shells of the cars. This epoxy would not shed any asbestos into the ocean. JCAA already had reports from the NY DEC that showed no harm from any of the asbestos that might be in the cars. We had also done an independent study and found asbestos was only a problem when in the air, not in water. At the request of the Governor’s Office, I checked with Dery and Cindy and made sure they had the same information I did. They said they had not known. Gary and I left the meeting with the hope we could work together. However, Monday morning Cindy’s release was included stating that asbestos in the subway cars would kill fish. She found an obscure study that stated dumping a huge amount of loose asbestos in a fish tank might have an adverse effect on fish gills. The subway cars had no loose asbestos, it was in the floor tiles and in epoxy between the cars. All the studies that were done showed there were no adverse effects of the asbestos on fish from the subway cars. Cindy was the one who violated the confidentiality of the meeting and did not inform either Gary or me about this release. I called Dery and he told me that Cindy did not want us to have a “heads up” and did not want to call us first. If you look at the first letter Cindy sent to DEP, November 2000, Clean Ocean Action and American Littoral Society were opposing subway cars even before she knew there was asbestos. In the end we lost half of the subway cars we offered since other states grabbed them up. Those letters were never sent to JCAA, and we found out due to calls from DEP.

- Jim Hutchinson should know that the articles included predated his article calling out Cindy. There was no secret about what was going on as everything was appearing in the press and the JCAA newspaper. At that time most newspapers had dedicated outdoor writers and subway cars was a frequent topic.

- Jim Hutchinson should remember that I called him on a Facebook post by Jimmy Donofrio that accused JCAA of working with Cindy Zipf to ban subway cars. When Jim told me he was working on his own article, I offered to discuss the issue with him. He turned me down.

- Jim Hutchinson should know that there is a pattern of behavior in the discussion about subway cars and about the current discussions about offshore wind. Cindy ignored the science about the lack of harm from asbestos in the water and used incorrect information to fund her campaign again the subway cars. The press releases about what was killing the whales follows a similar pattern. She was eventually required to disavow her earlier statements that the whales were dying because of the surveying done for offshore wind. Every other environmental group I know disagreed, but she used the issue again to fund her fight against offshore wind. People in the press should be skeptical when she issues these types of releases without appropriate scientific studies.

- Jim Hutchinson should do his own research by reading the January JCAA Newspaper and including information from Al Ristori and the then Commissioner of DEP, Lisa Jackson.

Below are the relevant articles as they were written over 20 years ago. For each, a link is provided to the JCAA archives as well as a link to the web archive of the Wayback Machine. (Links to the Wayback are to digital archives captured shortly after the articles were written and posted in 2001.)

Once melting glaciers shut down the Gulf Stream, we would see extreme climate change within decades, study shows

Superstorms, abrupt climate shifts and New York City frozen in ice. That’s how the blockbuster Hollywood movie “The Day After Tomorrow” depicted an abrupt shutdown of the Atlantic Ocean’s circulation and the catastrophic consequences.

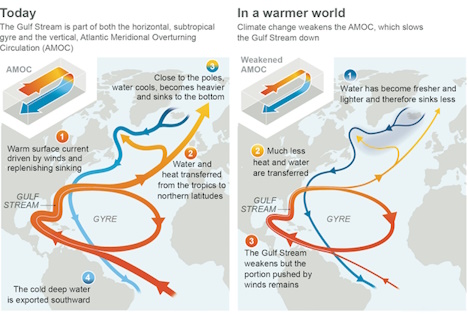

While Hollywood’s vision was over the top, the 2004 movie raised a serious question: If global warming shuts down the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, which is crucial for carrying heat from the tropics to the northern latitudes, how abrupt and severe would the climate changes be?

Twenty years after the movie’s release, we know a lot more about the Atlantic Ocean’s circulation. Instruments deployed in the ocean starting in 2004 show that the Atlantic Ocean circulation has observably slowed over the past two decades, possibly to its weakest state in almost a millennium. Studies also suggest that the circulation has reached a dangerous tipping point in the past that sent it into a precipitous, unstoppable decline, and that it could hit that tipping point again as the planet warms and glaciers and ice sheets melt.

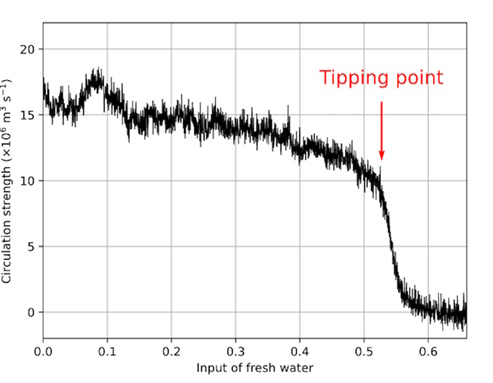

In a new study using the latest generation of Earth’s climate models, we simulated the flow of fresh water until the ocean circulation reached that tipping point.

The results showed that the circulation could fully shut down within a century of hitting the tipping point, and that it’s headed in that direction. If that happened, average temperatures would drop by several degrees in North America, parts of Asia and Europe, and people would see severe and cascading consequences around the world.

We also discovered a physics-based early warning signal that can alert the world when the Atlantic Ocean circulation is nearing its tipping point.

The ocean’s conveyor belt

Ocean currents are driven by winds, tides and water density differences. In the Atlantic Ocean circulation, the relatively warm and salty surface water near the equator flows toward Greenland. During its journey it crosses the Caribbean Sea, loops up into the Gulf of Mexico, and then flows along the U.S. East Coast before crossing the Atlantic.

How the Atlantic Ocean circulation changes as it slows

How the Atlantic Ocean circulation changes as it slows

This current, also known as the Gulf Stream, brings heat to Europe. As it flows northward and cools, the water mass becomes heavier. By the time it reaches Greenland, it starts to sink and flow southward. The sinking of water near Greenland pulls water from elsewhere in the Atlantic Ocean and the cycle repeats, like a conveyor belt.

Too much fresh water from melting glaciers and the Greenland ice sheet can dilute the saltiness of the water, preventing it from sinking, and weaken this ocean conveyor belt. A weaker conveyor belt transports less heat northward and also enables less heavy water to reach Greenland, which further weakens the conveyor belt’s strength. Once it reaches the tipping point, it shuts down quickly.

What happens to the climate at the tipping point?

The existence of a tipping point was first noticed in an overly simplified model of the Atlantic Ocean circulation in the early 1960s.Today’s more detailed climate models indicate a continued slowing of the conveyor belt’s strength under climate change. However, an abrupt shutdown of the Atlantic Ocean circulation appeared to be absent in these climate models.

This is where our study comes in. We performed an experiment with a detailed climate model to find the tipping point for an abrupt shutdown by slowly increasing the input of fresh water.

We found that once it reaches the tipping point, the conveyor belt shuts down within 100 years. The heat transport toward the north is strongly reduced, leading to abrupt climate shifts.

The result: Dangerous cold in the North

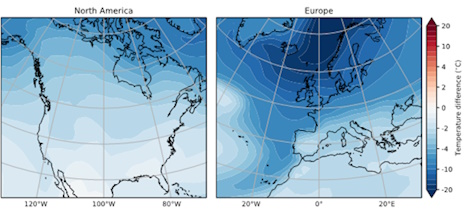

Regions that are influenced by the Gulf Stream receive substantially less heat when the circulation stops. This cools the North American and European continents by a few degrees.

The European climate is much more influenced by the Gulf Stream than other regions. In our experiment, that meant parts of the continent changed at more than 5 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius) per decade – far faster than today’s global warming of about 0.36 F (0.2 C) per decade. We found that parts of Norway would experience temperature drops of more than 36 F (20 C). On the other hand, regions in the Southern Hemisphere would warm by a few degrees.

The annual mean temperature changes after the conveyor belt stops reflect an extreme temperature drop in northern Europe in particular. René M. van Westen

The annual mean temperature changes after the conveyor belt stops reflect an extreme temperature drop in northern Europe in particular. René M. van Westen

These temperature changes develop over about 100 years. That might seem like a long time, but on typical climate time scales, it is abrupt.

The conveyor belt shutting down would also affect sea level and precipitation patterns, which can push other ecosystems closer to their tipping points. For example, the Amazon rainforest is vulnerable to declining precipitation. If its forest ecosystem turned to grassland, the transition would release carbon to the atmosphere and result in the loss of a valuable carbon sink, further accelerating climate change.

The Atlantic circulation has slowed significantly in the distant past. During glacial periods when ice sheets that covered large parts of the planet were melting, the influx of fresh water slowed the Atlantic circulation, triggering huge climate fluctuations.

So, when will we see this tipping point?

The big question – when will the Atlantic circulation reach a tipping point – remains unanswered. Observations don’t go back far enough to provide a clear result. While a recent study suggested that the conveyor belt is rapidly approaching its tipping point, possibly within a few years, these statistical analyses made several assumptions that give rise to uncertainty.

Instead, we were able to develop a physics-based and observable early warning signal involving the salinity transport at the southern boundary of the Atlantic Ocean. Once a threshold is reached, the tipping point is likely to follow in one to four decades.

A climate model experiment shows how quickly the AMOC slows once it reaches a tipping point with a threshold of fresh water entering the ocean. How soon that will happen remains an open question. René M. van Westen

A climate model experiment shows how quickly the AMOC slows once it reaches a tipping point with a threshold of fresh water entering the ocean. How soon that will happen remains an open question. René M. van Westen

The climate impacts from our study underline the severity of such an abrupt conveyor belt collapse. The temperature, sea level and precipitation changes will severely affect society, and the climate shifts are unstoppable on human time scales.

It might seem counterintuitive to worry about extreme cold as the planet warms, but if the main Atlantic Ocean circulation shuts down from too much meltwater pouring in, that’s the risk ahead.

Link to original article